“Understanding the Market Chasm”

What Makes Farmers Tick?

So why haven’t we experienced the revolution in agricultural technology that many are expecting to occur in the next few years? There are a lot of factors that should be considered in the analysis of the situation, some of which might include the following insights and observations:

So why haven’t we experienced the revolution in agricultural technology that many are expecting to occur in the next few years? There are a lot of factors that should be considered in the analysis of the situation, some of which might include the following insights and observations:

·

Growers are, by nature, cost managers as most,

not all, do not control the price of their finished products and can only

manage expenses as a means to achieve profitability. Many view something new as

simply an added cost of production. Farmers buy retail and sell wholesale.

·

Growers who are doing well financially will

rarely change their practices in the hopes of achieving even greater gains. It is

difficult to argue success.

·

Growers who are struggling financially will not

invest in some new technology unless absolutely forced into that decision. Most

farmers are “cash conscious” (taxes are filed as cash basis) and view the balance in their bank account as

a good indication of success or failure. You don’t buy what you can’t afford.

·

Change assumes risk and most growers are

conservative by nature and risk averse. Farming is already inherently risky when dealing

with the weather.

·

The average age of farm owners and managers is

56 and trending up slowly. The point being that many do not think in terms of

“technology as solution” in their decision processes. “Just Google it” is not in the

farmers’ vocabulary.

·

The majority of crops are harvested annually. A

producer has one chance every year to do everything right and turn a profit.

Changing the formula for success is not something that is taken lightly. You

get one shot every year and you can’t afford to mess it up.

This peek into the psyche of the American farmer should not

be a surprise to many who have experienced first-hand these behaviors. It may

be that this is an observation of human nature in general and not restricted to

those people engaged in the business of farming.

Not Just Growers Need to Change

The technologists should also assume some of the responsibility for the slow adoption rate. Many of these companies have entered the market with the latest wiz bang disruptive technology tool that only complicates the decision processes further. Generating more and more data may not be a solution to any problem. When so many new products only address a single or maybe just a few aspects of the total number of decisions that growers are making daily concerning pests, nutrients, genetics, water, equipment, labor, weather, marketing and many more, spending too much time on one challenge may not be the best use of a producers’ time. If the new “thing” does not simplify a growers’ life it will not be used for very long.

The technologists should also assume some of the responsibility for the slow adoption rate. Many of these companies have entered the market with the latest wiz bang disruptive technology tool that only complicates the decision processes further. Generating more and more data may not be a solution to any problem. When so many new products only address a single or maybe just a few aspects of the total number of decisions that growers are making daily concerning pests, nutrients, genetics, water, equipment, labor, weather, marketing and many more, spending too much time on one challenge may not be the best use of a producers’ time. If the new “thing” does not simplify a growers’ life it will not be used for very long.

Talking 'Bout a Revolution

What will it take for the changes to occur in farming that will truly revolutionize farming the way that hybrid corn did in the 40s and 50s or GMO soybeans more recently? Significant increases in yields, improvements in quality, optimization of crop inputs and greater profits for the farmer are within the grasp of the industry. Tech tools are currently available to enable huge efficiency gains in agriculture. Unfortunately, pulling all of the data from so many disconnected and disparate sources has not been easy to do. More importantly we are at the beginning stages in developing true decision making tools. Measure and monitor needs to migrate towards apps that control systems and hardware as they do in VRT. Morphing applications to those that optimize using predictive models will yield greater returns-on-investment as will the introduction of the final phase of automation where user interaction in the decision process is minimized substantially.

What will it take for the changes to occur in farming that will truly revolutionize farming the way that hybrid corn did in the 40s and 50s or GMO soybeans more recently? Significant increases in yields, improvements in quality, optimization of crop inputs and greater profits for the farmer are within the grasp of the industry. Tech tools are currently available to enable huge efficiency gains in agriculture. Unfortunately, pulling all of the data from so many disconnected and disparate sources has not been easy to do. More importantly we are at the beginning stages in developing true decision making tools. Measure and monitor needs to migrate towards apps that control systems and hardware as they do in VRT. Morphing applications to those that optimize using predictive models will yield greater returns-on-investment as will the introduction of the final phase of automation where user interaction in the decision process is minimized substantially.

Across the Great Divide

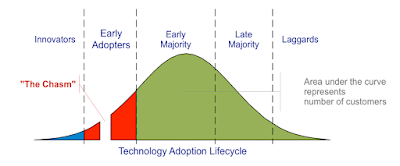

Geoffrey Moore, in his book “Crossing the Chasm”, took another cut at the adoption curve that Everett Rogers had hypothesized and inserted a gap between a preliminary and secondary group of Early Adopters. This gap, or chasm, demonstrates what many of us already know about the technology revolution that will certainly be in our future. Getting the market to leap across a great divide may require some actions that have yet to be taken by both the technologists and the growers. More on that later.

Geoffrey Moore, in his book “Crossing the Chasm”, took another cut at the adoption curve that Everett Rogers had hypothesized and inserted a gap between a preliminary and secondary group of Early Adopters. This gap, or chasm, demonstrates what many of us already know about the technology revolution that will certainly be in our future. Getting the market to leap across a great divide may require some actions that have yet to be taken by both the technologists and the growers. More on that later.

Managing Expectations

In the meantime, technology entrepreneurs will need to temper their expectations as to the adoption rate for their products and services as we evolve agricultural practices and processes over time. And there may be steps that can be taken to shorten those market growth timelines given an understanding of the grower persona and behaviors. The potential for success is clear. The path to getting there will be challenging.

In the meantime, technology entrepreneurs will need to temper their expectations as to the adoption rate for their products and services as we evolve agricultural practices and processes over time. And there may be steps that can be taken to shorten those market growth timelines given an understanding of the grower persona and behaviors. The potential for success is clear. The path to getting there will be challenging.