Transforming the Entire Food Ecosystem

Where is the “food” part of this blog? I have been remiss in

providing an explanation of the title for my discussions – Agri-Food

Technology. Let me take a moment to shed some light on this subject.

Optimizing the Chain

Optimizing the Chain

Possibly the best way to clarify this concept is to talk

about the food supply chain which is not

yet a value chain - but more on this

later. If you view food manufacturing in its’ entirety you get a sense of the

opportunity for optimization of the collective industries that make up this

dynamic continuum of agriculture and food. This ecosystem might not be broken

but it is a long way from being efficient.

Beginning with those companies that manufacture equipment or

crop inputs, including genetics, all the way to the consumer you get a sense of

what many refer to as “farm to fork”. Except in this case it is really “pre farm to fork”.

More with Less through GEM Data

How can a food and beverage processor benefit from

technology that their suppliers of raw product deploy? The answer is in the

data. And how can a grower benefit from sharing that data with their business

partners downstream from them? The simple answer is in the optimization of Genetics,

Environments and Management practices (GEM) that delivers better quality raw

goods resulting in better processing yields to their buyers who are willing to

pay for it.

All processors or food manufacturing executives can readily recite

the costs of production for each line item on their Income Statement. Containers,

ingredients, equipment, energy, labor, transportation, etc. (COGS), and, last but most

important and the largest figure of

all for first stage processors– raw product – is the one that typically receives

the least amount of attention from management.

Upwards of 40% of costs of producing a single can of peaches

can be attributed to the purchase of those peaches from the grower. Now if one

could somehow buy the same amount of product from farmers and produce just 1

more can of sliced juicy fruit or more than 1% more cases of finished goods

that money would go straight to the bottom line. No more effort. No more cost

(OK maybe the cans and other variable costs). Free peaches mean increased

profits for processors.

Give Me Your Watch to Tell You What Time It Is

Great! So now I have told most of you something that you

already knew. But how would you suggest that one go about getting free peaches?

Here it is again. The data.

Tomato processors have figured it out to some extent. They

know that better quality crops mean better processing yields overall. In the

case of paste manufacturing it is less water and more tomato (solids) that

drives improved output. There are other quality issues but for the most part it

the amount of solids that receives the lion’s share of the focus.

There are only three variables that can create a better

tomato. Genetics (seed, seedling), Environment (weather, soil) and Management

practices (crop inputs –nutrients, pesticides, water, labor, and equipment) and

the right combination of each of these can more consistently deliver not only

better quality for processors but better yields for growers.

Aggregation and analysis of the GEM data in and of itself

will not solve the problem of delivering a better “packout”. But combining this

data with production results can and will result in greater processing

efficiencies. There is, however, one operational requirement in order to

achieve the desired improvements.

Traceability Not Just for Recall Management

Without traceability, knowing where the product came from

(grower, farm, field, block) one cannot gain insights into what caused good or

bad processing yields. And without that critical tie between processing

performance and a particular products’ GEM there is no hope in determining “best”

combinations of GEM.

Value Chains Share

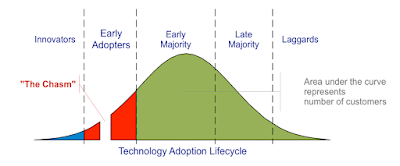

Our old nemesis CHANGE rears its ugly head once more. The supply chain requires a transformation

to that of a value chain. What this

means is that processors and growers need to establish a very different

relationship than the one under which they currently operate.

Our old nemesis CHANGE rears its ugly head once more. The supply chain requires a transformation

to that of a value chain. What this

means is that processors and growers need to establish a very different

relationship than the one under which they currently operate.

Chain optimization means that value needs to be shared between

partners. Where there are gains there should be compensation provided to

those who deliver those gains. The growers’ costs for collecting and managing

the data needs not to be simply covered but should result in the payment of some

sort of premium. Incentives drive behavior. Just ask my pal Melika. Ball? Cookie? Squirrel?